July, 1991

by Ken Johnson

Art in America

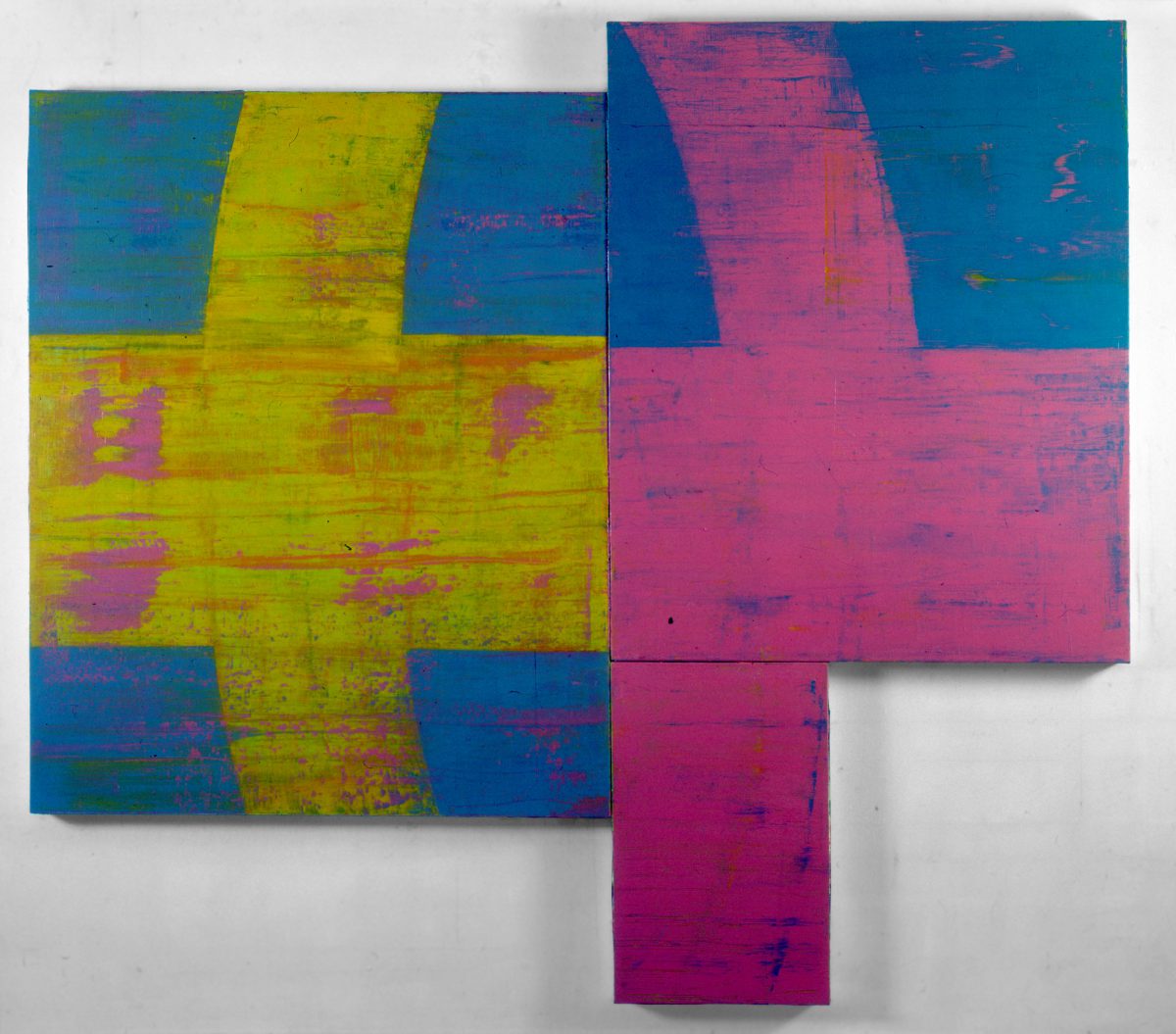

David Row. Tropicana, 1991, oil and wax on canvas, 92 x 102 inches

Two worlds collide to form David Row’s abstract paintings: a world of visionary geometry akin to Al Held’s and one of material sensuality like that of Sean Scully. The imaginal realm is present in wide oval bands and crisscrossing straight lines that suggest a perspectival geometry. There’s a sense of big wheels in cosmic space or some kind of vast heli- cal network. It’s not rendered with the kind of explicit clarity that you see in Held’s paintings—it’s more fragmentary and allusive—but nevertheless, the pictures intimate Platonic mysteries, as though they were depictions of archetypal structures of existence.

This transcendent vision is brought down to earth and obscured by Row’s invigoratingly playful, insouciantly daring manipulation of painting’s physical aspects. Each work has an infrastructure of three (or in one case, two) canvases of different sizes, and these panels tend to break up the consistency of the geometric representations. The separate panels are like mismatched pieces of a huge puzzle. (Overall dimensions range from around 6 to over 12 feet.) In one work, three unmatched horizontal rectangles, each bearing an arcing section of a big ellipse, are joined so that no outside edge lines up, which gives the grouping a feeling of propellerlike revolution. Furthermore, each panel adopts a completely different palette— one dark red and dark purple, one yellow and mauve and the third orange and yellow/green.

Another painting features horizontal purple-and-yellow concentric oval rings that are interrupted near the middle by a wide, vertical, blank yellow panel. The rings don’t line up on either side of the blank panel, which is mildly unsettling—you keep wanting to adjust things to bring them into alignment.

What especially grounds these images in physical immediacy is . Row’s paint handling: using a wide blade, he scrapes over still-wet paint to create a striated, multihued surface. Colors are intense. There are hot reds and oranges, caustic yellows and greens and deep purples and blues. Row scrapes across one panel into another, pulling color into the adjoining, differently colored space to create a streaking, blurred effect, and the way colors are scumbled over and under one another makes for a dazzling opticality. The paintings invite you to stand close and pore over the dense accumulation of painterly detail. There’s also a certain atmospheric quality: the scraped, complicated, textural skins seem weathered, steeped in history like old painted walls or the bodies of well-used trucks.

Pondering the way the visionary ideal is disintegrated and obscured by materiality, you may discern something metaphorical: perhaps the paintings are about how entrapment in the sensual can cloud spiritual perception. You may hope that in his engrossment in the physicality of painting Row won’t begin to neglect the thrill of mystic geometry. At any rate, as they stand now, these sumptuously handsome paintings engage you in a complex play of dualities: material and imaginal, unity and fragmentation, form and process, present and past, sacred and profane.