October, 2004

by Joe Fyfe

Art in America

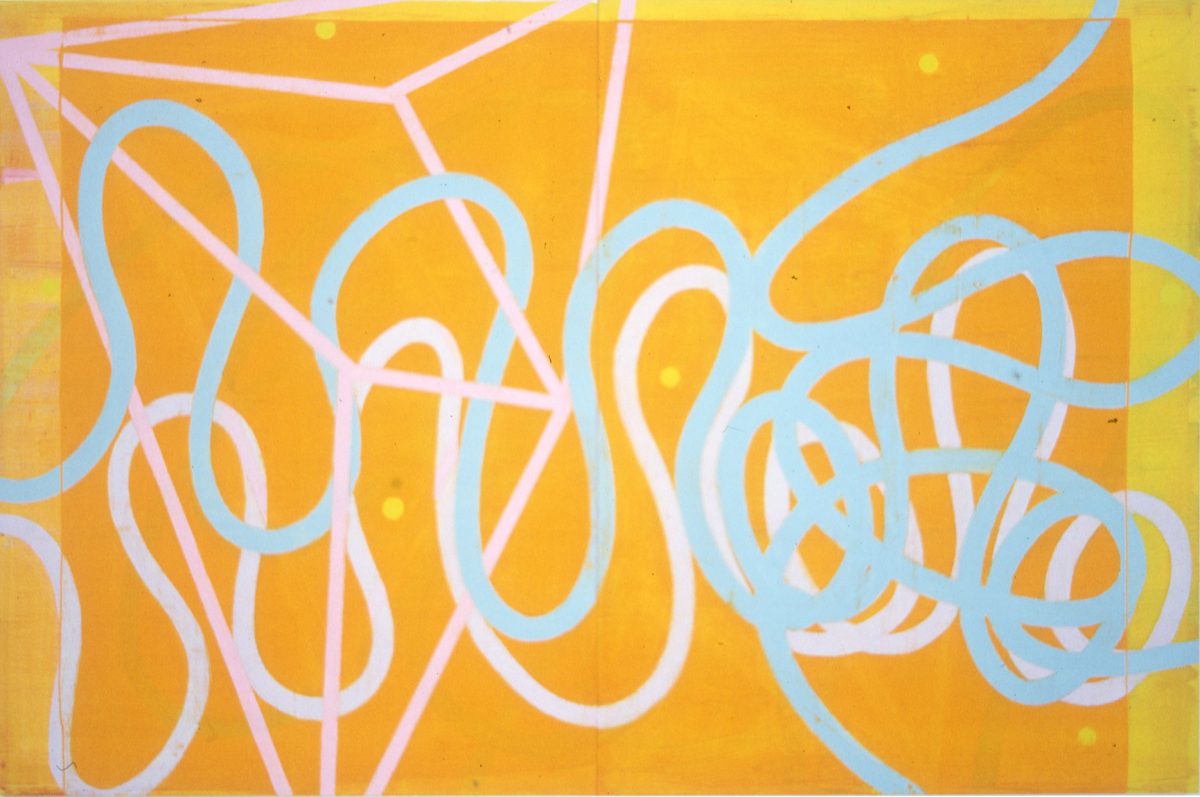

David Row: Waves of Desire, 2004, oil on canvas, 72 by 108 inches at Von Lintel

David Row has spent over 20 years devising abstract paintings that seek to capture the tenor and grit of contemporary experience. In the early ’90s, Row worked with abutted rectangular canvases onto which he painted curved bands immersed in planes of scarred, variegated surfaces that seemed to spur a kind of centrifugal movement. His use of astringently pretty colors, such as acidic pink and lime green, pushed the paintings toward a kind of industrial picturesque. Later in the decade it became more common for him to juxtapose his painted fields within one continuous rectangular support. These pictures feature interlocking areas of photographic blurriness and dragged paint applied upon smeared ovals and ribbon-like marks.

The overall sensation Row’s work produces is of a speedy muscularity. His aggressive cropping is reminiscent of the rapid editing of MTV and action movies. Another painter of Row’s generation, David Salle, once said that his own paintings were over when the viewer turned away from them. Row’s paintings, by contrast, are always on. The viewer almost has to catch them as they roar by. Row’s most recent paintings still have some of this quality but they are less frenetic and more luminous. This appears to be the result of his acceptance of the unity of the rectangle; he no longer breaks up the picture into independent painted areas.

In the 72-by-108-inch Waves of Desire, for example, Row paints a slightly smaller, semi-opaque version of the rectangular support within the picture plane only once, by applying a tangerine-colored field with a wide, flat knife. Calligraphic turquoise loops, one step removed from graffiti, thread their way across the horizontal plane as they partially obscure a paler echo of themselves. This doubling rhymes with the doubling of the large plane behind the two sets of loopy marks. A kind of low-frequency visual buzz is introduced by a silk-screened dot pattern. Used in some but not all of the new paintings, this device seems to embed the stiff, elongated gestures in faux texture.

Underpainting is visible in all the paintings in the show, reminding us that Row’s main debt is to Cubism’s transparent planes. There are moments in many of the works where the color seems set out on the canvas simply to be bathed in light. Row’s previous scrapings, croppings and abutted canvases now seem discardable devices on potential the way to what are his first genuinely open paintings.