January, 1992

by Demtrio Paparoni

Tema Celeste

“We have to recognize that the static hierarchies and meanings inherent in the language of classic abstraction are closed and no longer viable. This language has to be broken down and opened up again, its imagery has to reflect the fractured, provisional, and linguistic nature of contemporary life and thought.”

Demetrio Paparoni: In the 1950s abstraction was characterized by a markedly subjective and emotional quality, which often included metaphorical implications (think of De Kooning’s women or of Pollock’s use of the patterns traced with colored sandin the rites of the American Indians). In your opinion does abstraction today still accept this metaphorical dimension, or has it become essentially self referential? In the sense, for example, that a square is a square and nothing but a square, as was the case in minimal art? The ellipse that you use in your own works is’broken, in fact, from the viewpoint both of form and color. In recent years Mario Merz has constructed spirals on the basis of the Fibonacci sequence, where each entry is the sum of the two previous ones: hence], 1, 2 (1+1), 3 (1+2), 5 (2+3), 8 (3+5) and so forth, a sequence that also recalls the laws of biology. Smithson’s spiral, too, aimed at a concrete basis in reality. In the light of these experiences, do you think that contemporary art can establish a metaphorical relation with the laws of nature?

David Row, Theta, 1991, oil and wax on canvas, 91 x 164 inches

David Row: The truth is that we no longer perceive abstract form self-referentially. I’ve always had a problem with that anyway, so I’m satisfied with a less closed reading of abstract form. In my own work, I’m interested in abstraction because it allows imagery to exist independently, as objects and events do in the world, rather than being tied to depiction. And as a language, geometric form is communicable and has, potentially, a large and complex vocabulary. Now, because geometric form is relatively elemental and because the inclination of the human mind is to impose meaning, it provokes a wide range of associations. Managing the drift and inflection of these allusions within a thematic vein is part of the task. Choosing a language, a vocabulary, and a syntactical approach keeps them from being arbitrary, but a protean quality vis-à-vis meaning and allusion is crucial in keeping the imagery alive. We have to recognize that the static hierarchies and meanings inherent in the language of classic abstraction are closed and no longer viable. This language has to be broken down and opened up again; its imagery has to reflect the fractured, provisional, and linguistic nature of contemporary life and thought.

As you know, one of the main issues confronting contemporary abstract painting is the role that meaning plays, whether it takes the form of allusion, metaphor, allegory, or any other mediated communication. If these forms, particularly allegory, but metaphor as well, take on a one-dimensional meaning, then they are just as limited and inadequate as traditional representation. They don’t have to be. By definition, a concept is a general idea, one not limited in scope or application. I am convinced that abstraction is the language of this time, and language and content are inextricably tied together. This language is innately mutable. It has the ability to communicate on many levels simultaneously and to generate a myriad of subjective responses, much the way a street crime would provoke different interpretations from various witnesses. Painting is a social act where the viewer is not just a receiver but also an interpreter. If metaphors are to be drawn, it is here, in the space between the painting and the viewer.

The relationship you draw between the Fibonacci sequence and abstract geometric form is interesting. If this level of information can produce profound imagery, all the better. But the imagery is still the issue. Its source can be literally anything, but its transformation into the context of painting is either significant or it is not. And we only know that when we see it, image by image. The introduction of concrete information into contemporary abstract painting is one important change. Others include the abandonment of a Kantian ideal, the introduction of a fractured quality both within the pictorial language and related to the image itself, a sense of the provisional, and the legitimacy of subjective interpretation.

DP: Do you consider “new abstraction’ a Proper definition for much of that contemporary painting which brings about, in the absence of recognizable images, a deconstruction of the pictorial (abstract) language of previous decades?

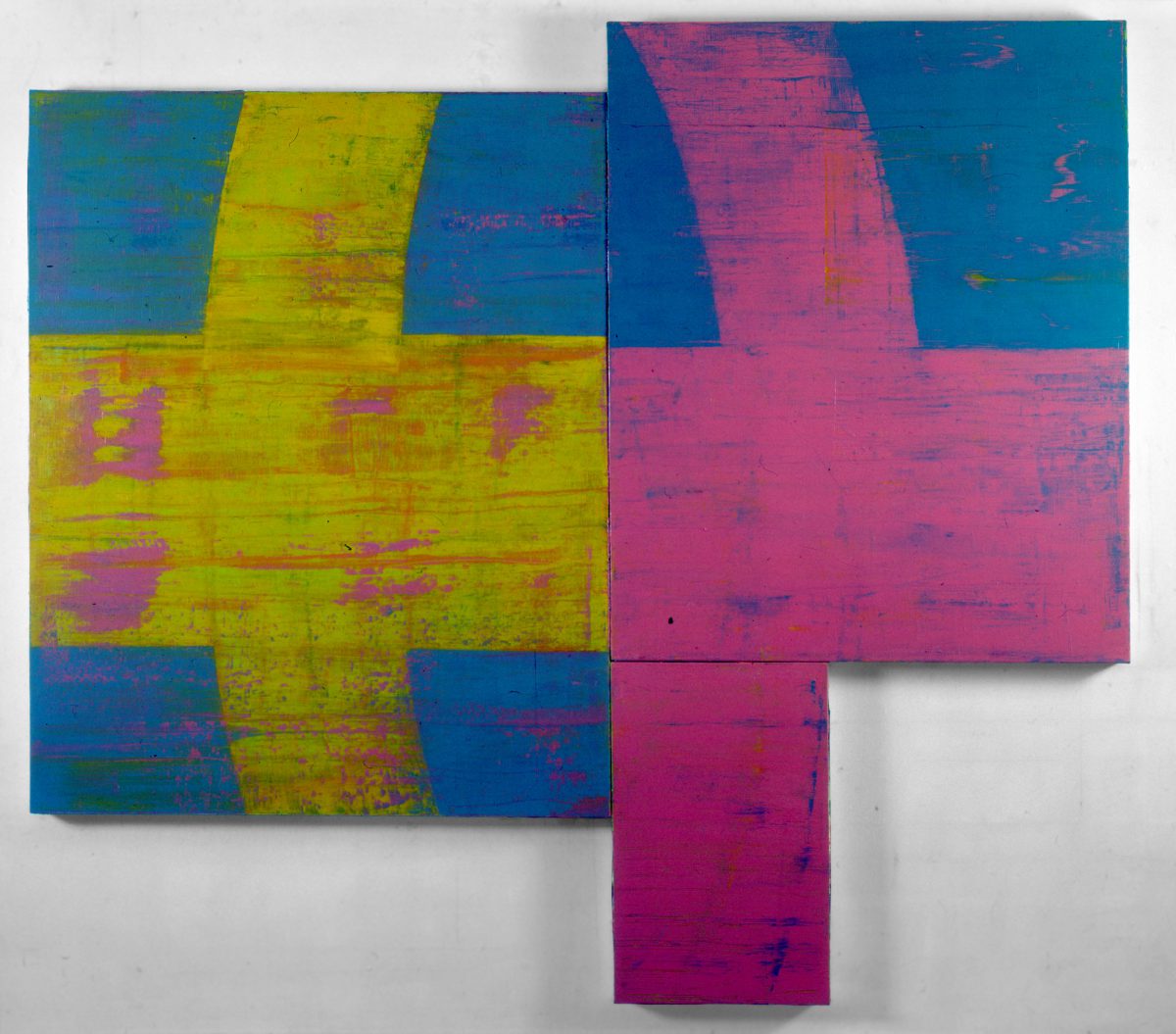

David Row. Tropicana, 1991, oil and wax on canvas, 92 x 102 inches

DR: A redefinition of abstraction is underway and it’s definitely “new’ in that many aspects of the endeavor called “abstract painting” have changed. Although a disparate project, abstraction is still the significant quality which so perfectly alludes to our culture now. And will, even more so, in the future. We are becoming a more visual society and one dominated by conceptual generalizations and abstractions. There has been a significant rupture in the intentions behind abstract paintings and in the way these paintings are made and seen. Among a number of issues upon which many contemporary abstract painters agree, deconstruction of both images and attitudes is a primary precondition to the development of new modes of abstraction.

DP: If one were to affirm that painting follows a destiny of its own, this would automatically preclude the possibility

of conceptualization and would be tantamount to saying that the abstract art of today is instinctive. I myself, on the contrary, see contemporary abstract art as closely bound up with the real, nearly as if it were a new form of realism. And in light of the theories put forth by Peter Halley, it has become abundantly clear how a geometric art can contain social and Political implications even more prominent than those found in a Painting that is realistic in the traditional sense. Can you say something about your own attitude toward conceptualization?

DR: Concepts (i.e. ideas) have always been an important part of my involvement with painting. Particularly now, it is important to investigate the conceptual possibilities for painting. Painting, now more than ever, remains an act of conceptualization. The important question is, “which concepts are more relevant and profound?”

DP: Do you think that a purely instinctive work of art is possible today?

DR: 1 do not believe in a specific destiny for painting, that being precisely the kind of Platonic/Kantian idea that I reject. Instinct is a tool, not a position. I do not know if there is a purely instinctive painting today, although I doubt that it is even possible.