1994

by Richard Kalina

Art in America

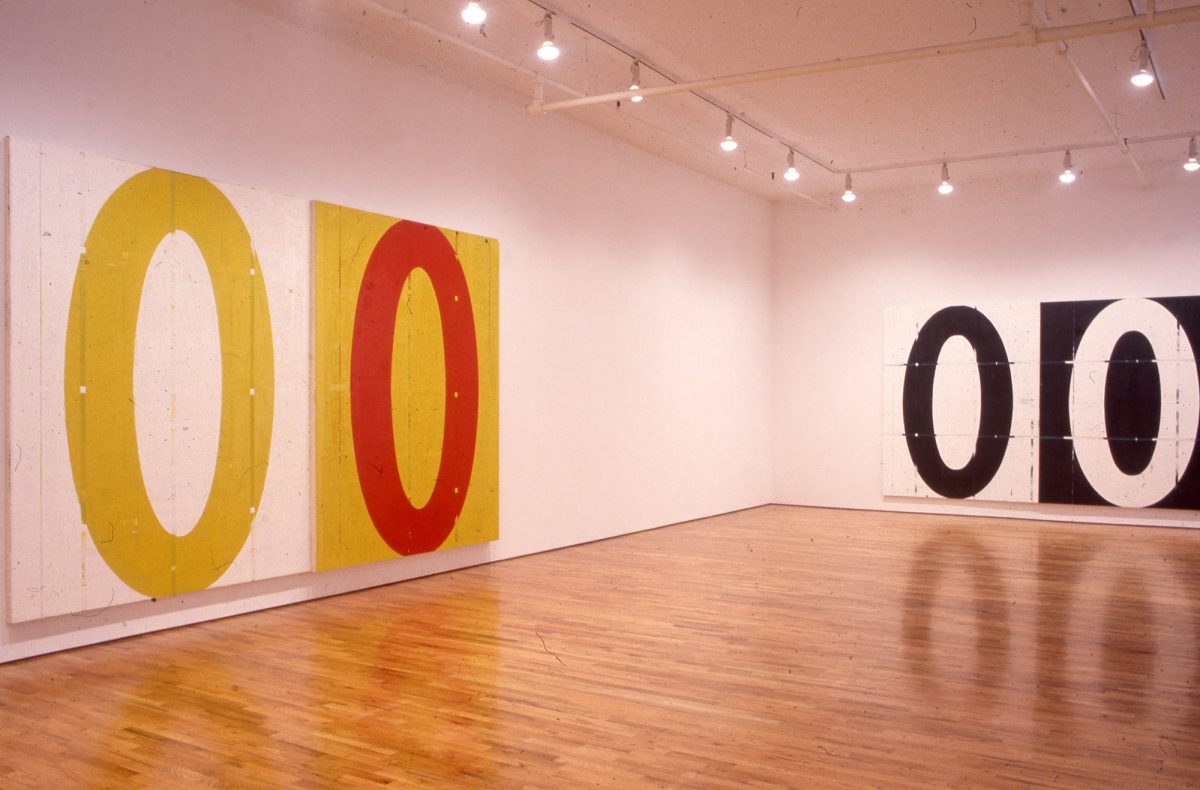

1993, David Row at John Good Gallery

David Row’s new paintings mark a significant departure for him. The open, multipanel paintings of his last show, with their cut-off ellipses, hot 1940s de Kooning-like color, and almost baroque carving of space, have been replaced by something more restrained and cerebral. Although they are qui eter, they are by no means Minimalist paintings. Row is narrowing the focus, creating a situation that allows us to play off an immediate, clear and graphic read against a slower, more sensual consideration of the nuances of composition and paint-handling.

These paintings are each made of two joined panels that match in their vertical and horizontal dimensions, although typically one panel is thicker than the other. This device emphasizes the objectlike quality of the painting and also creates a subtle optical warp. Placed on each of the panels, in a blatant figure-ground relationship, is a single vertical ellipse, cut here and there by the thin stripe of a grid. The ellipses are the first thing one sees in these works. Not only are they bold forms in emphatic colors— black, white, lipstick red, bright orange or acidic chartreuse— but they demand a literal reading: they are zeros or O’s. Look longer, however, and ambiguity starts to assert itself. The forms begin to lose their static, emblematic character, their one-to-one relationship with each other. In Ground Zero, for example, we see that while the chartreuse ellipse on the right is more or less centered, the black ellipse on the other panel is placed considerably to the left of center. In addition, the black ellipse is complete at the top, just kissing the edge of the canvas, but is cut off slightly at the bottom. This placement is reversed on the right, producing a subtle but powerful shifting of visual weight. The individuality of each of the panels is emphasized by the different whites used for the backgrounds, cool on the left, warm on the right, and also by the uneven disposition of the grid lines. These lines—the marks left when painted-over masking tape is pulled up—are either schematic divisions of the painting surface or indicators of the intuitive placements of the ellipses. They are a way of bringing the color of the ellipse out into the ground and also of including colors from the underpainting that were changed as the work proceeded.

Row’s surface is a kind of palimpsest, a layered record of his decisions, processes and manipulations. He uses stencils to delineate his forms, and the technique is one that is prone to fortuitous accident. We see slips and blurs, imprecise joins, pulled-up paint, and the ghosts of earlier ellipses. The paintings have a gritty, bruised feel to them. They seem in some way damaged, but all the more human for it. Row has taken on a difficult task. To combine the extremely bold and literal with the subtle and evocative risks misunderstanding. We are not used to both readings being given equal weight. That Row has undertaken this double-minded task, and with such affecting results, is testimony to his ambition and skill.