2017

by Barbara MacAdam

The Brooklyn Rail

On the occasion of David Row’s recent show, Zen Road Signs, at Locks Gallery in Philadelphia, Rail contributor Barbara MacAdam met with the artist in his longtime SoHo loft filled with examples of his art from various periods. The work—in different sizes and mediums—from prints to acrylics, oils, and encaustics randomly arranged—made an ideal setting for a conversation that meandered from the consistency of the 68 year-old artist’s career trajectory to the inevitable differences between older and newer works. We wondered where he—and any contemporary abstract artist—fits in the scheme of things today; challenged, aided and even sometimes inspired by technology.

Portrait of David Row. Pencil on paper by Phong Bui.

MacAdam (Rail): I wonder if you could talk about the trajectory of your art-making and the fact that you’re so instinctual and attracted to abstraction. It seems as though it’s not a choice.

David Row: No, I don’t think it is in a way. Artists make images from all different processes or ways of thinking, and for me, there’s just a way that I allow myself to make drawings; to come up with images and then decide whether those images are interesting, whether or not I have a plan. But I think we all have our parameters. A plan usually messes things up for me. It’s better if I just allow myself to play around with new images until I find ones that are more interesting than others. And I guess I’m more attracted to images that seem a little slippery, that are harder to pin down, whether it’s spatially or in terms of content or symbology or whatever. The plan is to go in the studio and see what happens.

Rail: And so then how do you start on something?

Row: I guess it happens differently, but I remember somebody told me a long time ago, “You go in the studio, and you start sweeping the floor, and before you know it you’ll be working.”

“Start” is a funny word, I guess, because I’ve always got different things going on—things I’m starting, things that are in the middle. It’s a little bit of a different story right now because I’ve just finished six months of working on this show that’s in Philadelphia, so I’m kind of taking a week or two off to try to recharge. But I guess the process really does start with sketches that are in the realm of what I’m working with, but allowing myself to just work, and see what happens. Those little sketches turn into ideas that I can use as a base for a whole lot of variations. And that can be 20 things, and the final thing can have aspects of a bunch of those—more than any one thing being the model.

Rail: So one leads to another.

Row: Yes, as I’m working on the painting I’m kind of starting out with things from one that seem more interesting than the others, but there are aspects of the others that can kind of come into that. That’s something that’s evolved over the years, and that works well for me if I don’t force it—if I just allow myself to go through that process. Then the other thing is looking. You know, you’ve got a whole bunch of stuff and you put it up, and over a few weeks, it just kind of wears on you. Whether or not you’re really feeling as excited about it as you first were.

Rail: Well you have a very distinctive vocabulary—actually, very geometric. Have you ever done any figurative work?

Row: Oh yeah, I did. Very early on I did. I decided I was interested in painting pretty early on; maybe when I was 15 or 16 I started to get a little bit serious about it.

Rail: Where were you when you started painting?

Row: Well my family was living in India at the time. That was a big influence of course. You know, color in India is really something, and it had a huge influence on me. I was just interested in making things without an idea about what that might be. And I was working by myself, I didn’t have any good high-school art teacher or anything like that.

Rail: But you had materials?

Row: I had the materials, basically. I’m not sure exactly what my age was when Henry Geldzahler did that show at the Met, New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970, I have the catalogue still. That was a big show—There were figurative things, there were abstract things. I had been making some figurative and some abstract paintings. In my stress at the moment I really had no idea what I was doing, but when I saw the Geldzahler show it changed me. That was the moment when I wanted to be an abstract painter. I saw the de Koonings and the Pollocks, the Klines and Newmans, and I thought, this is a whole world that I don’t know anything about, and it seems so interesting and exciting, and that was the first thing that made abstraction kind of a possibility. I was in school, in classes. I was an undergraduate at Yale, and they would say, “Make a still life or make a landscape.” So I did some of that. But I never knew what to do. You know, I’m not a storytelle

Rail: That’s a good point.

Row: I like a lot of movies and I like a lot of pop songs that have a narrative, but my work is always more enigmatic. In a funny way, that enigma is what it’s about. I really think that is a kind of openness to the image being seen differently. I think that’s always been the thing about abstraction. I remember looking at Mondrians when I was in high school and thinking, “what the hell is this about?” You know, some work demands a kind of attention and a kind of thinking that seemed much more interesting than me telling a story.

The real issue for me ultimately is space for the viewer. I think that’s what it was for me. When I was in that Geldzahler show, I felt like I was involved in those paintings. I wasn’t being told something, or I was being told so many things that I had to sort out what I was being told. And for me, the important experience of painting is being a viewer, and what it is to be interested as a viewer. And I think that’s obviously a very personal thing. Everyone has their experience of being a viewer, and of what they want to see.

David Row, Zen Road Signs, 2017. Courtesy Locks Gallery, Philadelphia.

Rail: Or what they can see. You think of all those factors too, what their color sense is, whether they’re color-blind, what their vision is.

Row: Vision may be the big word. It is interesting that you should mention it, because I’ve met a number of artists who have said to me, “I’m color blind in this way, I’m color blind in that way,” and I find this kind of interesting, too.

But where were we?

Rail: The different ways of seeing and how the audience partakes of what you do, which you can’t control.

Row: Which you can’t control. And I’m talking about this first experience with American Modernist paintings, and all of that. It took me till later to work back into cubism or fauvism. So I grew up on modernism. That was the thing. And went from all the things I’m talking about right up through minimalism and conceptualism and a lot of other things. But there were qualities of modernism that I slowly began to have problems with. And I think the larger culture kind of did, too—you know, the utopian aspect that it could actually change society. I do believe that it can change individuals, by the way, but I don’t know whether you can change a whole society. But I’m just also nervous about utopia. Utopia is always someone else’s utopia.

Rail: There’s sort of no such thing.

Row: Yeah, and also if somebody imposes it on other people . . .

Rail: Then it’s not a utopia.

Row: Right, and I think the progress thing was always also something that, in my experience… painters move all over the place, but I think it’s really a rare artist that has a beeline from where they start to where they end up. It’s not linear.

Rail: No, but in a funny way your work is quite consistent.

Row: Well it is at a certain point.

Rail: Your vocabulary is firm, that’s what it is.

Row: Well it’s interesting, because, even talking about the later work, the curvilinear work, it’s clear to me now that it’s harder for people to see what’s going on. I think the turning point for me in terms of vocabulary and what I wanted to deal with was re-investigating Brancusi at some time in the mid to late ‘70s. I saw him talking about something in the work that wasn’t just limited to the work; but also somehow he talked about this much larger vision, and I thought, “Well, that’s just a fantastic idea.” And then I started to think a lot about what painting had been historically, and there are an awful lot of situations you can point to where painting seemed fated or determined to try to deal with what it can’t do—like, depict an angel. So painting’s a funny thing. We think of it as two-dimensional, not three-dimensional, but it’s more of a psychological space. I think that it happens formally in that two-dimensional plane, but it’s so much more than that; it’s almost like entering into some 100 percent totally different world.

And that Brancusi idea connected me with painting. And the kind of problem of painting. I think it was part of the way I was formed as an artist, where painting had actually been declared dead a few years earlier. And that worked into this thing about what’s possible and what’s not possible. But Brancusi was the turning point. That was when I realized I could have a vocabulary that talked about certain things and didn’t have to change the vocabulary all the time.

I think there’s something to the idea that you work on something for a long time… I don’t even like to think about the fact that it’s been 40 years since I started working on these things, but I’m very slow; I need a lot of time. And I think maybe that’s true for a lot of visual artists?

When I got out of grad school and came to New York, I didn’t have people in my studio for a long time, like maybe two years.

Rail: Really?

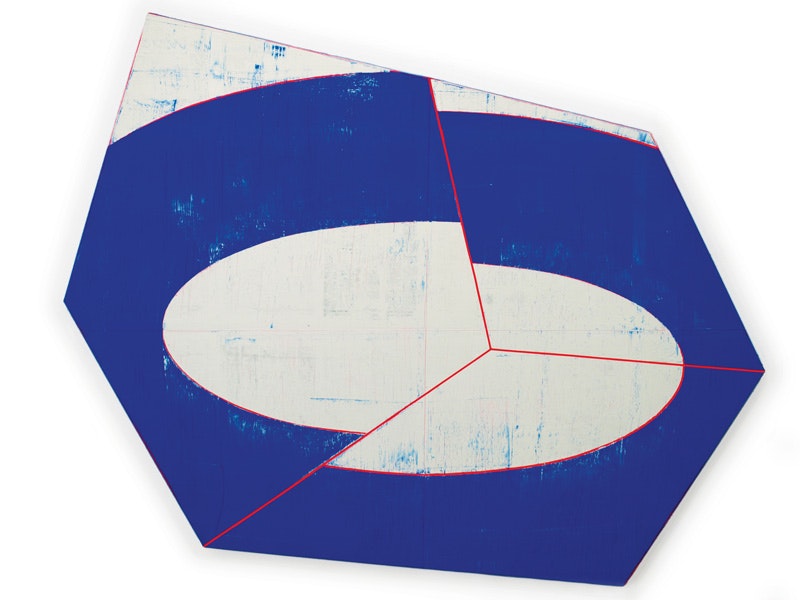

David Row, Big Pink, 2017. Oil on canvas, three panels. 56 x 113 inches. Courtesy Locks Gallery, Philadelphia.

Row: Nobody in the studio. At first I was showing a little bit in group shows, but I was really not showing, and was trying to get myself into a position where I was trying to see exactly what I wanted. I spent those years in a very high-profile grad school situation with people like [Brice] Marden and [Larry] Poons coming to the graduate school and kind of being in the studios, and it was very intimidating. They had a kind of authority that you didn’t have. And I think that what I needed to do in that sort of super-slow period afterwards was to be alone with the work and to figure out what that work was. So the first one-person show I had in New York was literally eight years after I got here.

Rail: What year?

Row: 1987 I think was that show on Bond Street with John Good.

Rail: So it began with John.

Row: Yeah. Well I had a show at 55 Mercer, but 55 Mercer at that point was always a two-person show. I had the back room. There was one other show, Art Galaxy. Do you remember Art Galaxy?

Rail: Oh Yeah, that became Barbara Flynn’s.

Row: Well Barbara started it; she was running it at the time. So I guess it’s true that I had a couple of other shows. But Barbara Flynn probably wasn’t too much earlier than John Good, no more than two years. But anyway I think of myself as being very slow, needing to take a long time.

Rail: I first saw your work at John Good on lower Broadway. It was probably around 1990.

Row: There was one in ’87, and one in ’89. That was a great space.

Rail: It was a great space.

Rail: The gallery must have been a great experience for you in a lot of ways, despite any anxiety you may have had. I mean, it really was a community of people doing variations on things that related to one another.

Row: I think there’s something about when you’re starting out, and you’re feeling around, and a lot of people your age are feeling their way through things—as confusing as that is, in retrospect is also kind of the most exciting time. So that was a good time for me, and I was ready to show, and I hadn’t been showing until very close to that time, so that was good. I think there’s something about when you have your work in the studio, and the work is supported by all the other work in the studio, and all the things you collect that you have on the wall and all that, it feels very homey; you have all your stuff supporting you. And the moment that you show something publicly you have to deal with that outside, and you get a glimpse at it objectively. And that’s also a really important moment.

Rail: Then I wanted to ask you about Al Held and his influence.

Row: Al Held was really huge for me. Al was my adviser when I first got to graduate school. He came in every week, and it was like scorched earth. It was so brutal, and so amazing. We hadn’t even finished the first semester when I said, “You know, Al, this is not really working for me.” and he said “Oh, ok fine, see you later.” and he never came back. He just left—I was shocked that he didn’t come back. I had said this one thing, and he had said ‘Oh, see you later,’ and I didn’t really talk to him again until the final critique when I was graduating. It was one of these things in “the pit,”—I don’t know if they still do this—it was in the Rudolf building, and people would look down; it was kind of a public event. They’d stand in line at the top and they’d listen, so it was a little intimidating. And the teachers who got up first to talk about my work were all negative. And I was thinking, “Boy, this is brutal; there is nothing good here.” And then finally at the end, Al stood up and said, “Well, I think you could go wrong, but I think there’s a lot of possibility in this work.” It wasn’t effusive or anything but for me it was like, “Wow, ok.” I think it’s the first time he’d seen the work. So then I didn’t see Al for a few years, but then I ran into him near his studio, and he said, “Listen, wanna come up to the studio?” I said yeah, and that was the beginning of a long, sometimes tumultuous friendship.

Rail: Was he a difficult man?

David Row, Zen Road Signs, 2017. Courtesy Locks Gallery, Philadephia

Row: He was all intellect. He loved ideas, and he loved debate, and he loved to talk about things. There were times when I would meekly disagree and it would get sometimes a little heated or edgy and I’d think, “I can’t believe I did that,” and then the next day it would be fine. He just loved ideas and loved debate, loved the idea that underneath great work, there are serious ideas, and you really have to push the work, own the work, whatever, to make those ideas blossom, to make them be there visually. He was just a great, great teacher to me, but the funny thing is he was a teacher to me long after I left school. When I was in school, Lester Johnson was the first teacher that I was kind of magically impressed by. I was in a drawing class; it was his drawing class, a graduate class, and I asked if it would be okay if I came in to draw. He said, sure. So I was sitting there drawing, and I was obviously not very good at it. He came over, and he had these big fountain pens; he drew a little rectangle at the top of my page, and he drew the model. I think it was about 10, 12 strokes, and boom, there she was, this perfect, plastic image of the model. And that was magic for me. And so, that was part of that early figurative education, and I learned a lot from that. Even from William Bailey. We ended up not getting along at all, but I learned about looking at classical painting. But I always knew that it wasn’t where I wanted to be. As far as school was concerned I would say Lester Johnson and David von Schlegell most interested me. I didn’t have too much interaction with David but when I did, it seemed he left me with a lot to think about.

It’s funny, but through junior high school and high school I never connected with an art teacher. Somehow everything that I was doing was exactly what they didn’t want to see or talk about. So the fact that I persisted is kind of perverse.

Rail: You had other interests too, didn’t you? Certainly your time in India, sports, and music, and it would seem from your work, geometry.

Row: You know that cultural thing, for me, I just can’t overemphasize. I was 13 when we went to India and I had never even imagined any kind of culture that was so different from mine. And it wasn’t even learning about that culture, it was being conscious of my [own] culture because of it—the contrast.

Rail: And then you were confronted with the fast-moving digital world.

Row: It’s very frustrating. But you know this thing about the digital; on a certain level it really does fascinate me, because you’ve got everything in the digital language. You have written text, you have images, you have every kind of calculation that you could ever want to do mathematically; it’s all in the same language, so there’s a kind of unity to it across disciplines that I must say is fascinating. But personally, I am just so completely literal. I remember being at a print shop, I was working on some lithographs (Tamarind), and I went in to talk to the master printer and said, “You know, Bill, if I do x, y, and z, what does that do in terms of the final product, and Bill gave me an answer something like, “what it means is this, this, and this.” So I went back to my little cubicle and started working with that in mind. And Bill came in, a couple hours later, and he said “What are you doing?” I said, “Well I asked you this question about process and structure…” and he said, “I thought you were speaking theoretically.” I said, “Bill, I am never speaking theoretically.” [Laughter.] I am completely literal and direct, that’s who I am. That’s why painting is perfect for me, because it’s so literal and direct. You do have to deal with the medium, and the medium has a mind of its own, and a phenomenological reaction to whatever happens to it, and so you’re in a conversation with that, but that’s different from a complex machine or a complex process. I really see it as a very direct thing in terms of the way I work. I’m not theoretical about it at all.

Rail: What about visually, how does your visual perception of the digital affect your work? I mean it must a little bit—or does it not?

Row: Well, I remember we used to have a Xerox machine in my wife, Kathleen’s Designspace, and I used to take an ellipse—the first ellipses I drew I used to draw with nails on the floor, that old system [where] you put two nails in and you put a string on it and then you pull it and it makes an ellipse. Then at a certain point the machine in Kathleen’s studio became something I could use to blow it up or down, I could manipulate it. But that’s kind of a whole tiling process; it’s really a relatively primitive thing. But in terms of your question, there did come a point at which, well . . . here’s a computer, you can just draw an ellipse. But, I’m always blowing them way beyond what I could do with a computer, outside of some system I don’t know about. Like a real mathematical ellipse is there now, and I have to admit, that in making the paintings, I don’t really care about its “real” mathematical-ness. I have this giant collection of stencils, and every time I go to use them, I think, “Oh I have that stencil, I’ve got one that big.” But I’m always manipulating them to get something out of them that makes them probably not very purely mathematical. Obviously that purity doesn’t interest me particularly.

Rail: What attracted you to the ellipse?

Row: Well I thought a lot about what geometry is in painting, and it occurred to me pretty early that an awful lot of it (like Mondrian) is just straight lines, even in Malevich. I thought, there are curved lines in geometry, but it became clear to me that the circle was not interesting. . . . I think the main reason is that the ellipse is such a slippery image, you know, is it a circle tipped in space? Does it have illusory space? is it a symbol or a letter? Is it a symbol of a mathematical figure? That openness was really what I loved.

Rail: It’s open and a symbol of openness.

David Row, Undertow, 2017. Oil on canvas, three panels, 70 x 86 inches. Courtesy Locks Gallery, Philadelphia.

Row: Yes and once we got to that level of the symbol of openness, it opens up this whole other thing—it’s slippery in a different way. It’s also a sound, a vowel sound. This connects back to what we were saying about modernists—you know, Donald Judd is somebody whose work you can’t help being incredibly impressed by, and I was. But it was pretty clear that he wanted to dictate how the work was seen. And I never really approached art that way. Whenever something is didactic, I just go away. If there’s no space for me to participate then it’s not so interesting. So my choice with the ellipse is so much part-and-parcel of that, that images are open and slippery and hard to pin down. If somebody wants to say, “is your work about x” or “what is your work about?” If you say x, then that’s what the work is about, and what I really want to steer clear of is this idea that there’s a fixed meaning. And that really relates back to what we were saying about narrative. That problematic-ness to me is so much more interesting than a story.

Rail: Well you want to feel free to move around in an image, or, do we call it an image then?

Row: To give the image its autonomy, to let the image have an active role.

Rail: And the ellipse is sort of a symbol of that, too, being that kind of infinite shape. And I was also thinking of skating rinks… actually in all of your work you think about action, or you feel it.

Row: There is a thing about movement in almost all of it. The thing that occurred to me when you were talking about the symbol was the idea that if you tip an ellipse on its end, and it looks like a zero or a letter-form, if you want to get involved with the symbolism and the meaning, you can’t represent nothing, in the same way that you can’t representinfinity. It keeps that image from being didactic. So all those things—openness to interpretation, and a sense of representing something that can’t be represented—those things really interest me. I think some people see those things as perverse. But to me it’s very Zen.“

Rail: And the observer has to fill it.

Row: We’re in such a different age from when I grew up in terms of that relationship to painting. I think images in general now—think about Instagram—it’s asking a lot in this day and age. . . there’s a fastness. But that sense of “wasting time,” is interesting to me, too, There’s a lot of time when you’re working that you’re kind of just day-dreaming—just kind of allowing things to come up. So wasting time for me is so important. But yeah, I think we’re in a different culture now, we’re not in a culture where people think about spending a lot of time on one thing.

Rail: Well, I guess you are and you aren’t. Let’s see… you have landscape, architecture—I mean not literally, but the sense of planning, of town planning . . . and then music, which I didn’t know that you had actually studied.

Row: Yes, I grew up in a family that was much more musical than I was. My mother sang in the choir of every church we were ever in, and played piano, and my oldest brother is a musician. My next oldest brother played cello for a while but then decided he didn’t want to compete with the oldest brother. But there was a moment…You were talking about movement in the paintings, and I know people see kind of literally in the paintings, but I think that comes from music. I love all kinds of music, and I listen to music pretty much constantly. I like to think of the movement in the paintings as really coming out of that.

Rail: It becomes inherent movement then, doesn’t it? It’s not intentional, it’s built in.

Row: And these other things you’re talking about—I never thought I would be an urban planner, for instance, which my father was. I never thought too much about his effect on me. I was very close to my father, we got along very well, but I never thought about our relationship having an effect on my work in some way. It took me longer to see that. I remember how my father had a way to see a city, and whenever we went to another city with him, we’d take a bus tour, and then walk— walking, walking, walking. You know, he’s the one who told me about Jane Jacobs. He came from a different point of view and education in terms of urban planning, but he was very much in tune with the idea that the whole point of a city is people, and how they can move around and work in it and play in it. I’m not sure that there’s any particular way to talk about it in terms of the work, but it has certainly affected me in terms of how I think about cities, and probably also the fact that I love New York and don’t want to leave New York. Yes, all these things in one’s background add up, and it’s pretty hard to parse them out. I do remember one story of my father, I was probably a freshman in college, maybe a sophomore, and I said that I was pretty seriously thinking about being a painter. He’s immediately like, “How about architecture?” You know, something that he can relate to.

Rail: Well I think there is that sense in your work.

Row: Structure is a part of it. And you know, architecture is a good word for it, but I think of it more as about structure. People have talked sometimes about surface qualities in my work. Well, painting has a surface, it has a skin, it has that. It’s always gonna have one kind of surface or another. And I do believe in that dictum that everything in the painting—from the skin, in—is important. But by the same token, the structure for me is much more important. I know an older artist, who’d been around for a long time, and who really surprised me one day when he said, “Well your work is all about surface.” I was shocked, because I really do think the structure is the most important aspect. The surface ends up being what it’s going to be being based on structure.

Rail: You know we didn’t really talk about color yet—another elephant in the room, and then I was thinking about Albers.

Row: Yes, yes, he was still at Yale when I was there; he wasn’t teaching. He had a studio in the basement of the Art and Architecture building, and the story was that he changed the fluorescent light bulbs like once a month—you know these light bulbs last like 20 years, but he changed them like once a month, and he worked under fluorescent light.

Rail: Oh I didn’t know that, that’s interesting.

Row: So he was there. I think he was a really important piece of that bigger puzzle in that school. We have the Albers book, the big silkscreen thing, and we love it, and I’m sure it’s been a huge influence on me—but I was very frustrated by it when I first encountered it. It took me a long time, and it really took me messing around with other people’s theories (Itten, Munsell et al.) to really appreciate that Albers had done something completely original in terms of thinking about color. But at the time I had such a hard time going from that theoretical cut-paper thing to how I actually used color. And ultimately my attitude toward color is that it’s this infinite system. There’s an infinite number of colors, and every color has its own emotional quality, its own temperature. And the great thing about Albers is that as soon as you bring in another color, you’ve got a completely different situation. You’ve suddenly got things interacting and you don’t have just that one quality.

I think ultimately for me I want just that quality—kind of like the show that’s up now at Lock Gallery—‘blue and no other color’ or ‘white and a color,’ a color with white or black. Because it allows that colors’ quality not to be diluted. I guess as I’ve gotten older I’ve come to feel that no matter what I do to manipulate that color, that quality is better than anything I could invent. All the associations with a particular blue, all the emotional landscape, whatever thing you could think about in your background that relates to that color, is super powerful. But I have to be completely intuitive with color. It’s so huge, that I just have to approach it on an emotional, direct level. If I start to get tricky with it I’m screwed.

Rail: Well your color is kind of magnetic. Your lime green, if we want to call it that, is really wonderful.

Row: I call it that all the time, and it has become a kind of a color association. I do think that there are colors that are in-between two colors, and they do have all the qualities I was just talking about but they’re in-between. That’s one of them.

It’s green and yellow, or blue-yellow-and-white, or whatever, but it just becomes this thing all its own. And that’s what I’m attracted to.

Rail: Well it’s sort of interesting too, going back to India and some of those colors, and the dance of colors.

Row: And I think, again, I was 13, and I was overwhelmed by the sensuality of that color. I just could not believe it. And when you go from one state to another in India, you go from—maybe this is less true now, I haven’t been back in a while—but you went from one culture to another culture. All the saris are different; all the colors are different, all the patterns, in the same way the cooking was different, and it was a new dialect or a new language.

Rail: Really

Row: You couldn’t believe how rich it is. But I have one experience that has just stayed with me for a long time. They used to have these tanks filled with water, and outside of one of them, close to where we lived in Kolkata—there were people who would dye things. They would dye something in a pattern and then leave it in the sun. And if I left in the morning, often, they would have laid out this huge piece of cotton with this color pattern on it—one color—and I’d come back a few hours later or in the afternoon, and it was the complementary color. It had been red when I left and green when I got back, and it was the same piece of cloth. It was the sun and the curing of it. It’s a culture that loves color—the more the better; the deeper, the brighter the better.

Rail: I was looking at the covers of some Albers books, and he disciplined those colors, right? But they’re there. And I was sort of shocked when I thought about that.

Row: Very German, haha—discipline everything. But I love Albers. And talk about digesting images quickly and moving on, the older I get the harder it is to move away from them, because you begin to see what’s happening. And it’s not unlike the [Ad] Reinhardt show that was just up at Zwirner. You walk in, and you kind of know what’s gonna happen with Reinhardt, but then it’s richer and more interesting than you thought it would be. It was this huge feast of blue that you couldn’t digest in one shot. It was just way too much. But also you could stay with those paintings and watch that color change, or watch your brain change the color.

Rail: Also, looking at the Locks show, how do you feel those paintings connect with your earlier works, while also extending your ideas? They do seem to open things up a little bit, right?

Row: Yeah, I think so. You work on things for so long, and sometimes you’re not even conscious of how you’re returning to something. And what’s happening between the ellipses and these shapes-the quartz—started longer ago than I thought, 2011 I think. In the six-year development of that particular body of work, a couple things happened that opened things up.

First of all, I think the surface is more present, and the paint heavier, which also makes the color richer, deeper, more saturated. There’s also a way in which the parts of the painting are not locked together as much. They’re a little more physical in each distinct area. The insides, say, of the ellipse—you’re more able to read that as a thing, not just a negative space behind a form, but actually as a thing. There’s a way in which the parts are kind of open and jiggled and not completely fitting together. And I think that openness is a combination of those two things, the surface and the way in which each part is almost an object that pulls off the surface. The other thing is the under-painting. There’s always been under-painting in my paintings, but I’ve allowed myself to preserve a couple of moments of the pure under-painting, and I think that also gives it air. And I think in general in those paintings there’s more coming through.

I’m very happy with a couple of things about that show. First of all I’m much more confident about playing with the orientation of the shapes. I think at the beginning I had a reading of how the shape ‘should be’ or ‘wants to be,’ and now I’m kind of open to the paintings’ position being a choice that I wouldn’t have made in the past. And, for me personally, they’re a little less stable than they were; they’re a little more outside the architecture. That makes them better too. The other thing about this show at Locks is that I realized there’s something musical about how the columns break up the space, and I like the idea that sometimes the painting is behind the column. I wouldn’t have thought about that, earlier in my career I would’ve thought that was a bad idea. But there’s a musical quality, there’s a quality as though the center of the space is another space, and a space with a different light, and almost a shadowed light. And that contrast of being inside the columns looking to that outside space where the paintings are reminds me of being in that Italian architecture where you’re inside the building but there’s an outside space. There’s something about it that I’m very happy with. It’s so hard to know how work is going to be in a space, and I think artists are maybe more deliberately dealing with that. One thing I’ve learned is that the dealers, museum curators, know their space, and they’ve dealt with a lot of different kinds of work in that space. And it’s important to respect that. I had an experience earlier on with Ascan Crone Gallery in Hamburg, it was the first show I did there, and Ascan was always really amazingly nice to me…I got there and he had hung the entire show. But he had this space that was all plaster walls, so when he decided to hang something, he had to kind of set something. I came in and was like “You know, Ascan, I don’t think this is right hanging in the space.” And he said, “Okay, okay, take them down and figure out where you want them, we’ll re-hang them.” So I spent two or three days moving that work around, and I ended up back the way he had it. And it made me realize that this man knows his space.

So I think of myself as pretty good at…maybe all New Yorkers who live in loft spaces are…kind of judging a space, and knowing how, projecting three dimensions in your head. But ultimately it’s like color. You have to be in it to know.