June 24, 2001

by Chris Schull

The Witchita Eagle

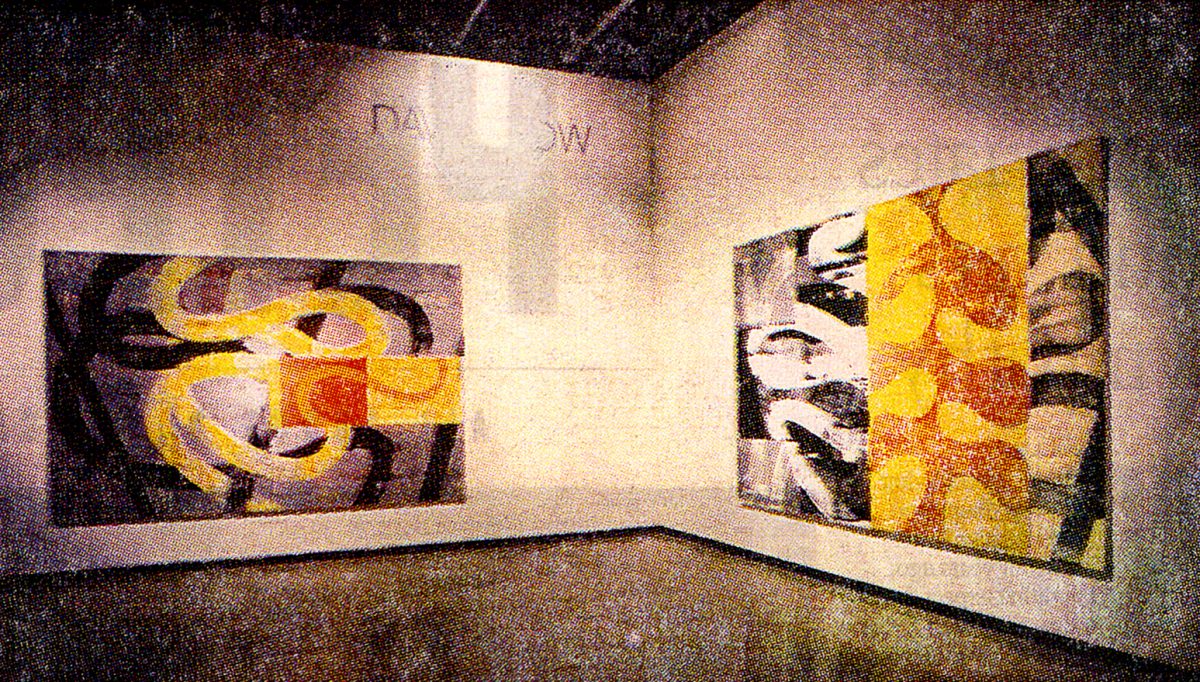

Two paintings in David Row’s `Ennead” exhibit at the Ulrich Museum at WSU. Courtesy the Ulrich Musuem.

His prints and paintings at the Ulrich Museum may be abstract, but they are all about feeling.

One of the common criticisms of modern art is that some of it looks as if a child could do it. A jumble of squiggles and dabs writhe on the canvas: a broad slash of color bisects an empty background; large sqaures of contrasting colors are arranged with geometric precision, as if done on graph paper.

This assult of a myriad of styles, all confidently called “art” by critics and curators supposedly in the know, makes even enthusiatic onlookers take pause. If this a god art, why can’t I immedialty see it as such.

Kevin Mullins, curator of exhibitions at the Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of An at Wichita State University, understands that sentiment.e also believes contemporary painter and printmaker David Row, whose work is hangng in two rooms in the Ulrich’s upstairs gallery, is the real deal, an insightful artist whose work resonates even with skeptics.

“There always is that sense of the emperor’s new clothes — you know, ‘Are you trying to pull the wool over my eyes? That is just a bunch of squiggles,” Mullins says. “There are a number of real basic building blocks abstract art or any art in general — you know, line, composition, form.”

“And what an abstract artist does is do away with a reference of the real world and concentrates on the basic elements that make up a painting.”

Visitors to Row’s exhibit, “Ennead,” on view through Aug. 12 might initially be confounded by the work — six monoprints and a large wall-drawing in one room and three large, bright paintings in another. After all, the images Row paints — his artistic vocabulary — are a collection of snaking, loopy lines, the same stuff regularly drawn in kindergartens everywhere.

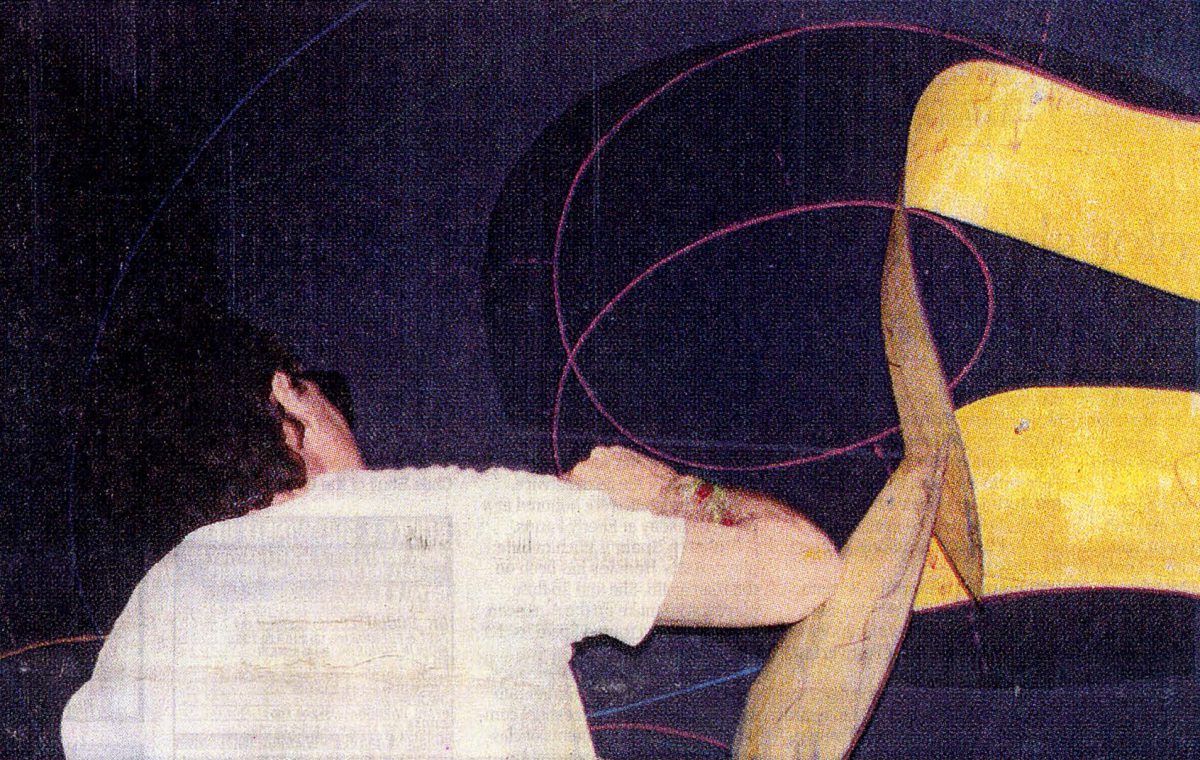

David Row uses stencils, right, to trace elliptical lines onto a wall-drawing at the Ulrich Museum. Courtesy the Ulrich Musuem.

Why is Row’s work art and the other scribble?

“When you look at these prints, I think anyone would see that there is quite an amount of control, that all these marks are very accurately made,” Mullins says. “It is not random, chaotic or haphazard. It is very, very controlled.”

The lines in Row’s work are not improvised doodles. Each curving, looping line and each bulbous, amorphous shape is actually coldly calculated.

“All those different lines are made from templates that had been cut out of a type of cardboard,” Mullins says. “There was something that was very thoughtout and planned, not random at all.”

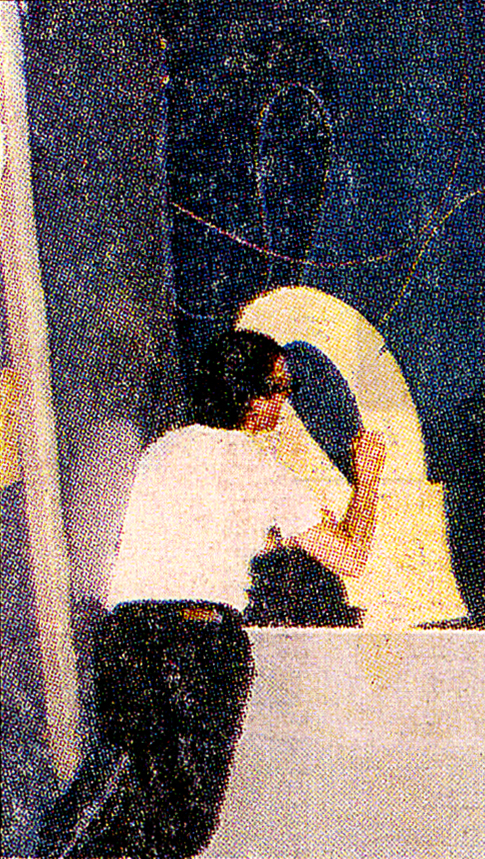

In the first room of the “Ennead” exhibition, all the snaking lines that wind around the six monoprints — and the thin, neon, chalk-like lines that flit and twirl across the wall-drawing — were made using nine different ellipses, or parts of those nine ellipses.

“I made these automatic gestures with my eyes closed, and then I use the templates to reproduce that automatic, intuitive gesture,” Row explains. “Once I do that, I can make that gesture any size.”

In other words, first Row scribbled, then he organized those impulses. He chose nine different sections of those scribbles to be the ABC’s of his work in “Ennead.”

In creating the brightly colored lines on the large, gray wall-drawing, he says, “I have a whole group of templates on the floor in front of me and I start with a segment of an arc, and then I pick up another template and a segment of that gets

used, and then I put that aside and I pick up another template. I don’t know where I am going. I am just following my nose.”

A sense of conviction and continuity flows back and forth between the monoprints and paintings in “Ennead” because each is created using a defined set of arcs and curves; each is connected through a similar artistic vocabulary.

Artist David Row uses stencils to trace elliptical lines onto a wall drawing installed at the Ulrich Museum at WSU. Courtesy the Ulrich Musuem.

“‘Feels right’ is a very important thing,” Row admits. “You see a Vermeer painting and you can’t even imagine how it was made or doing it yourself, and yet you don’t have to be told it is great. It feels right.

“In terms of people approaching (my work) and having all sorts of questions about it, (Willem) de Kooning (the abstract expressionist artist) once said, ‘The fact is, we don’t live in a self-evident world.’ Things are not necessarily self-evident. That is just the way it is.

“When we talk about this (show), and I am very specific, that is one thing. But I would like the work to he read on an intuitive level. I would like people to approach the work on the level of, ‘Something feels right here’ rather than being totally analytical.”

For Mullins, that is exactly what first attracted him to Row’s paintings when he fast viewed them in a small gallery in New York City in the 1980s. Now Row is well-established and well-collected — a famous and fairly important artist.

But for Mullins, who knows Row’s importance and is proud to have brought his work to Wichita, the paintings and prints in “Ennead” all about the feeling are ‘The reward is having a show up that every morning I come up to look at,” Mullins says. “To me, that is what good art is all about, something that holds your interest, that you want to go back and look at again.

“This is a show that I linger in when I am making sure the lights are all working.”